25 Jul The shocking results of the 1977 Israeli elections and “Revolutionary Government”

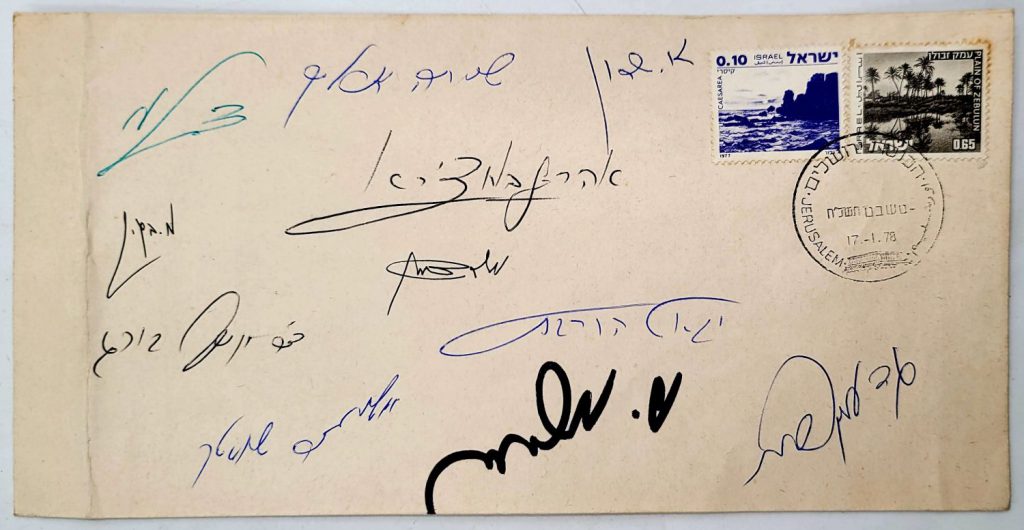

Rare Document

An exciting document of the 1977 “Revolutionary Government”

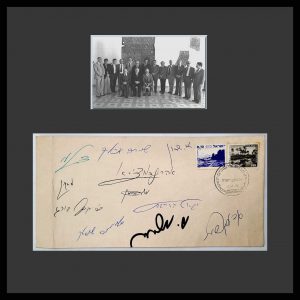

Envelope sent from the Knesset in Jerusalem with original signatures of Likud members “Revolutionary Government”, including Menachem Begin, Moshe Dayan, Yosef Burg, Arik Sharon, David Levy and others.

Professionally framed with a photo of the Likud government in 1977

It was May 17, 1977. Israelis crowded around their black-and-white television screens for the national election results. At exactly 10 p.m., the face of Haim Yavin, the normally unflappable anchorman of Israel’s lone TV channel, appeared, looking very flapped indeed. “Ma’hapach!” he intoned, a variation of the usual Hebrew word for “revolution.” It was a softer term Yavin had come up with on his way to the studio. He later explained that he hadn’t wanted to cause panic.

The result was shocking. There had never been a change of governing party before in Israel. For the first time, Mapai, the socialist party founded by David Ben-Gurion and now led by his disciple Shimon Peres, was out of power.

Perhaps the worst accusation they had leveled against Begin was that he was a capitalist. That was a bit ironic for a man who was born broke and stayed that way all his life. Even as prime minister, Begin bought his suits on a payment plan.

From Israel’s founding until the 1977 vote, Mapai or its affiliated Histadrut labor organization tightly controlled most of the country’s agriculture and industry, health care and social welfare, infrastructure and development, education, housing and radio. No detail was too small for the socialists: In 1964, the government banned the Beatles on the grounds that they would subvert the morals of Israel’s pioneering youth.

Begin, who had spent an instructive year in a Siberian Soviet gulag during World War II, was skeptical of such power. He had simple instructions for his finance minister, Simcha Ehrich: Free the economy and make life better for the common people (by which he meant Likud voters).

Ehrlich, who owned a small optics factory in Tel Aviv, was a short, sixtyish man, pinked-cheeked, fastidious and laconic nearly to the point of silence. He had served on the Knesset Finance Committee for many years, but he was at heart a party hack and a dealmaker. Ehrlich was devoid of formal education or economic training. The Israeli media began calling him a follower of Milton Friedman, the free market guru who had recently won the Nobel for economics. But Ehrlich, who couldn’t read or write English, didn’t know Milton Friedman from Kinky Friedman.

A few months before the 1977 election, in an address to a business group, Ehrlich set out his core economic belief: “Israel is too small and too poor to maintain a welfare state.”

He was right about Israel’s size (population at the time: 3.5 million) and its relative poverty. In some ways, the economy had more in common with the Communist satellites of Eastern Europe than with Western countries. But as welfare states went back then, Israel was pretty good. It provided free public schools and cheap university tuition; affordable, high-quality public health care; subsidized food; available work with strong labor protections; and decent social services. But the price for all this was confiscatory income taxes, high tariffs on foreign-made luxury goods (almost anything fancier than a can opener qualified), low incomes and poorly made local products.

Like Begin, Ehrlich thought that Israel’s economic potential was being stifled by misguided ideology and political self-interest of the socialists. His mission was to turn things around. Rarely has anyone been less suited for a task.

When Ehrlich arrived at the Finance Ministry, he came alone. The senior staff, largely Labor Party loyalists trained in Keynesian economics and fond of the status quo, gave him very little help. But Ehrlich plowed ahead with his agenda: deregulating foreign currency, lowering import barriers, allowing the Israeli pound to trade freely, cutting government spending, shrinking the bloated bureaucracy, and weakening the power of the labor by introducing mandatory arbitration.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.